Can you hear me now? Edison’s Talking Machine

December 12, 2018

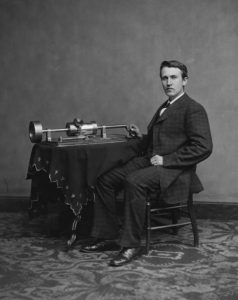

On December 7, 1877, Thomas Edison entered the New York offices of the Scientific American, a popular scientific magazine that happened to be one of the emerging inventor’s favorite periodicals. Unlike earlier occasions, this visit was not about discussing the latest telegraph device or telegraphy’s ever evolving technology. This day was different; the young inventor found himself on the cusp of international stardom, as he had in his possession a machine that could talk– the very first of its kind!

The day before in his laboratory, Edison shocked his staff when his newest creation reproduced the nursery rhyme Mary had a little lamb. The experience came as an absolute surprise, leading an ecstatic Edison to write:

“I was never was so taken back in my life. Everybody was astonished. I was always afraid of things that worked the first time.”

Inside the office, Edison’s fateful moment had arrived– could he repeat his successful demonstration from the previous day? As curious staff members gathered around his bizarre apparatus, Edison began cranking the handle, and almost immediately it began repeating the inventor’s pre-made recording. Utterly amazed, the journal’s editor later stated that “the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial goodnight.” As a result, the indomitable young inventor from Menlo Park became the first person to both record and reproduce the human voice, a remarkable accomplish that had eluded many within the scientific community during much of the nineteenth century.

According to Curatorial Registrar, Matt Andres, the tinfoil phonograph was “very much based on Edison’s initial idea for recording and playback of telephone messages for what he called his “speaking-telegraph” machine. In fact, the two diaphragms used on Edison’s earliest version of the phonograph are a direct result of his research on the subject of telephony and acoustics.”

The machine is a rather simple device, in that it features a grooved cylinder attached to a cross-shaft with a screw pitch and was turned by a hand crank. John Kruesi, one of Edison’s top machinists, initially created two diaphragms, one for recording and another for playback based off of earlier research. Soundwaves from a person’s voice caused the recording needle to vibrate thus indenting the tinfoil. Upon playback, the second needle followed the same trajectory as the first, subsequent contact with the indentations produced vibrations that allowed the playback mechanism to reproduce the soundwaves. For several decades, scientists had been investigating a variety of complex methods to reproduce sound, so many were completely stunned when they learned about the machines sheer simplicity and relatively easy operation.