Maid of Chautauqua

By Karen Maxwell, Horticultural Specialist

For most of her life, Mina Miller Edison may have enjoyed her July 6 birthdays on the shores of Lake Chautauqua in western New York, in one of the first of the gingerbread- style cottages that collectively would become known as the Chautauqua Institute Historic Village. A recent visit opened the door to a richer and clearer understanding of the person to whom a smitten Thomas Edison referred to as “The Maid of Chautauqua.” After meeting the Miller family in Chautauqua, with her parents’ approval, Thomas Edison was allowed to take the young Mina Miller to the White Mountains in New Hampshire, where he would later propose.

Since its founding in 1874, originally as the Chautauqua Lake Camp Meeting Association, today the Chautauqua Institute is open for nine weeks annually from the end of June to late August. The entire community has 7,500 homes situated on 750 acres, with the Institute as its nucleus, dedicated to nondenominational advancement and understanding of the arts and religion.

The village is a dense labyrinth of narrow streets winding around hilly terrain, packed with gingerbread-styled cottages – some small, some quite ostentatious but all beautiful and colorful with attractive landscaping when space permits. There is a post office, library, bookstore, amphitheater, cultural halls and parks. Apart from pavement and automobiles, it probably looks much like it did 100 years ago. Narrow roads and compact houses leave little space for vehicles, but there is a “wave it down” free tram or bus always available in season, adding to the village charm.

Locating the Lewis Miller cottage, even with map in hand, proved challenging on my first visit a few weeks ago. I noted a Miller Way, Miller Park, Miller Avenue, Mina Edison Drive … and then found the cottage at last located at 24 Whitfield (I think)!

Arriving at the corner of Whitfield and Vincent Avenues, bordered by Miller Park, I finally met Betsy Burgeson, Supervisor of Gardens & Landscaping, already hard at work in this garden – one of 35 or so that she oversees for the famed Institute. Struck by the lovely little cottage, I refrained from running up the front porch steps to peer inside and quickly joined Betsy in the front gardens as I tried to temper my excitement of being in Mina’s northern garden at last. Finally realizing that we had abruptly jumped into the gardens, I turned around looking for Fred (my better half). At the bottom of the driveway, a stately gentleman in his summer straw hat was introducing himself – Jon Schmitz, Archivist and Historian, Chautauqua Institute who gave us an entire day to study and research and opened the archives just for our visit and continues to be an invaluable resource.

Prior to this visit, my knowledge of Mina Miller Edison’s contributions to society had been extrapolated from histories, newspaper articles and lore in and around Fort Myers. I now know that everything Mina Miller Edison was and all she accomplished, was molded right here on the grounds of the Chautauqua Institute and at this very cottage.

It is my understanding that Thomas Edison did not visit Chautauqua very often, but this is clearly a place Mina loved and treasured. Certainly, her famous husband’s name helped Mina secure the most influential and sought-after speakers to present at the Institute and helped to raise funds and awareness for her important efforts including literacy, religion, wildlife, conservation and gardening.

Mina’s father, Lewis Miller – a co-founder of the Institute – had the cottage prefabricated in Akron, Ohio, in Swiss- chalet-style, painted white with a raspberry-colored trim. It was built on the hillside to overlook the Founder’s Park and Lake Chautauqua beyond. The intimate cottage was hardly of sufficient size to accommodate the Millers along with their 11 children, so a large tent was initially erected in the yard to house the Miller boys and it once sheltered the overnight stay of President Ulysses S. Grant in 1875.

It was not until 1915, at 50 years of age, that Mina purchased the cottage from her 10 brothers and sisters, afforded the opportunity by her husband’s financial success. In 1920 she began a major renovation of the home and grounds, having acquired several abutting lots to create more garden space. She changed the building’s color scheme to its current gray and turquoise. In 1922, she eliminated the second floor “women’s dorm,” opting for private bedrooms and removed first floor walls to create a single large living area for entertaining her family. Though she modernized her small kitchen, Mina enjoyed a private family table at the Athenaeum Hotel just down the hill, where she and her family and guests took all their meals. Cooking was never one of her pleasures, but gardening certainly was!

Quite recently, Archivist Jon Schmitz located a garden plan, designed in 1922 by Ellen Biddle Shipman, for the Miller Cottage. As the original Miller parcel was confined, it is believed that Shipman encouraged Mina to acquire three lots abutting the rear of the Miller property. An old boarding house was torn down, and its stone foundation was saved to become the back garden wall for Mina’s new garden – providing a perfect backdrop for Shipman to create her signature water feature and a place to sit. It is here that Shipman fulfilled Mina’s desire for a place of refuge, reflection, inspiration and rejuvenation. On the small urban-like parcel, Shipman was able to include a semi-formal corner, a naturalized woodland area full of native plantings to attract the birds that Mina adored, and areas of perennials, shrubs and trees to boast an ever-blooming garden.

With Jon’s discovery of the Shipman plan, and under Betsy’s leadership with assistance from the Chautauqua Bird and Garden Club, many of the original plantings have been identified including beech trees, rhododendrons, dogwoods, hemlocks, ferns and mountain laurels and they serve as sentinels along the beautiful stone walkways that transition the gardens to the cottage – true to the Arts & Crafts period of design.

Unlike our Moonlight Garden, also designed by Ellen Biddle Shipman, the plants that Shipman chose for Mina’s New York garden corresponded to the climate zone. Old gardens can never be precisely reproduced with the limitations of new diseases, invasive species, introduced pests and local changes in micro-climate. Guided by Mina’s detailed record keeping, Betsy has done an extraordinary job restoring these charming grounds that surround the cottage. Notwithstanding the removal of walls of hemlock, adjusting for new water run-offs, locating historic plants; and tackling the garden by creating zones, her efforts are truly wonderful and fellow gardeners can appreciate the extent of the work involved.

The plant lists saved by Mina specified quantity and pricing and each list is stamped with the approval of the designer – Ellen Biddle Shipman. We cannot begin to imagine what it would cost today to purchase and install every plant depicted on the Shipman planting plan for the grounds of the Miller house.

In anticipation of her time to be spent with me in the Chautauqua garden, I brought Betsy a framed copy of Shipman’s plan for the Moonlight Garden – so we could compare notes. What both gardens have in common is the overwhelming density and high maintenance aspect prescribed by Shipman. Save to say, not a single plant in the Chautauqua garden is represented in our Moonlight Garden. Despite those requirements, Mina was evidently quite pleased with the results, as she would go on to hire her again in a few years to design the space once occupied by Thomas’ original laboratory in Fort Myers.

The Miller Cottage remained in the Miller family until it was purchased in 2016 and donated back to the Chautauqua Institute the same year. In 1965, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, with Charles Edison overseeing the dedication, and it remains the only cottage in the historic village with this designation. Most of the exterior furniture is original to Mina Edison as is 90% of the interior furniture and appointments per the detailed records maintained by the Archivist. Today, the house is actively used by Institute staff, so it is not open to the public, but the grounds are accessible for viewing when staff are not in residence.

Following our time at the Lewis Cottage, Mr. Schmitz invited us to the archives, where he had pulled boxes and boxes of files and records pertinent to Mina Miller Edison and Ellen Biddle Shipman. And that treasure trove my friend, is a story for another article!

Color photos courtesy of Karen M. Maxwell.

Black & White photos courtesy of Chautauqua Institute Archives.

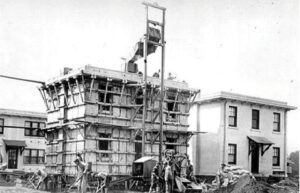

Cemented in History

By Matt Andres, Curatorial Registrar

“Thomas Edison invented cement?,” quipped a bemused visitor standing amongst his brethren of fellow tourists. “Wow, is there anything this guy didn’t invent?” After chuckling, I calmy resumed my colloquy, “as a historian and Edison Ford curatorial staff member, I can unequivocally say without a doubt, Edison did not invent cement my good man. Please do not post a headline stating Edison invented cement on social media” – half laughing but also serious in my remark.

The Ancient Greeks, Macedonians, and Romans all used some type of crude cement as a building material in constructing infrastructure for their primary city states, the nucleus of each of their opulent and expanding empires. After the fall of Rome, it became sort of a lost architectural artform for centuries until its reuse during Europe’s Middle Ages.

The earliest form of Portland Cement was developed and patented by Joseph Aspdin of England in 1824. The material had similarities to Portland stone which was quarried on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. This form of cement would become the industry’s predominant type by the late 19th century.

Edison’s involvement with cement came as a derivative of his ill-fated iron ore venture of the 1890s. He poured himself into this industry by initially selling waste sand from his ore business. By 1899, the perpetually inquisitive inventor began investigating viable ways to retrofit technology for reuse in working with cement. He ultimately made plans to extricate himself from his iron ore debacle and use his gigantic rock-crushing machines in manufacturing a tangible product.

His machinery produced a much finer powdery material than his competitors and his patented long rotary kiln proved so successful in creating a high-grade Portland cement that he eventually licensed this technology to others in hopes of increasing its durability and usage during the earliest decades of the 20th century. Subsequently, this led to overproduction, however, which caused profits to decrease as a direct result.

Edison built an automated plant in Stewartsville, New Jersey that eventually produced cement utilized in numerous buildings, roads, dams, and other important miscellaneous structures, such as New York’s “basilica” (the original Yankee Stadium) dedicated for and used by its most successful baseball franchise, the Yankees. A 1923 report indicates Edison’s Portland Cement Company used more than 30,000 cubic yards of concrete, 30,000 cubic yards of gravel, 45,000 barrels of cement, and 15,000 cubic yards of sand in building the stadium. Perhaps literally making it the house that “Edison built” instead of Yankees star slugger George “Babe” Ruth.

In 1917, Edison was granted a patent for a clever way of mass-producing concrete houses using a single-pour construction method and a series of molds that could essentially create all its integral parts: exterior, interior walls, roof, decorative ceilings, various room partitions, bathtubs, floors, and stairs. He hoped to transform America’s housing market by offering an inexpensive alternative that was fire resistant, impervious to bugs, and easier to keep clean and sanitary. Unfortunately, for Edison, his $175,000 framework builder kits were expensive, heavy, and contained a vast array of parts and components that left home builders less than enthusiastic about their future potential.

Emboldened by his vision for the potential uses of Portland cement, America’s greatest inventor even executed a patent on July 18, 1911, for concrete furniture, which included bedroom sets, pianos, and his beloved phonograph. Not all of Edison’s ideas were great as evidenced by over 500 failed patent applications throughout his career. Edison abandoned this quest after capitulating to the realization that concrete furnishings were neither stylish nor nomadic friendly.

Overall, he received 49 of his 1,093 United States patents directly related to cement, its manufacturing equipment, and processes. Learn more about Edison’s work with cement by visiting the Edison and Ford Winter Estates museum and see artifacts related to this industry and more.