Clerodendrums

By Karen Maxwell, Horticultural Specialist

In the array of tropical plants we grow, a most fascinating group is the family Clerodendrum and though it still hasn’t found its way into many southern gardens, Clerodendrum thomsoniae* has been at the Edison and Ford Winter Estates for at least 90 years, based on the plant inventory for Seminole Lodge, dated 1931. In the Moonlight Garden, we grow seven varieties, most of which bloom throughout the winter months and several that bloom almost year-round, which speaks highly of its value for seasonal gardeners who desire gorgeous flowers during the winter months.

The family includes shrubs, small trees and vines, some of which are aggressive enough to be used to create a colorful border fence, but because the grouping is so diverse, there is probably a Clerodendrum perfectly suited for your garden or planter. It’s not only gardeners that should be excited by this plant group, but scientists around the world have recently focused more closely on the potential medicinal value of several species of Clerodendrum as it is indigenous to some of the most heavily populated regions of our planet – Africa, China and Pacific rim countries as well as Australia.

According to the “Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine,” an international forum for medical researchers, there is growing excitement to expand exploration of the 280 chemical constituents of this family, including 43 flavonoids which have been isolated (things in fruits and vegetables that keep us healthy). Clerodendrum compounds have been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine and the international medical community is looking to understand and evaluate the merits of research that indicate these plants may be able to play a significant role in the treatments of inflammation, cancer, bacterial infections, obesity and much more.

Clerodendrum are classified in the Lamiaceae (mint) family, making them cousins to lavender, basil and rosemary whereas they were formerly part of the Verbena family (lantana, porterweed, and verbena). Now this makes no sense to me, as I once learned that plants in the mint family were easily identified by their square stems, aromatic qualities and often medicinal uses. The very name Clerodendrum breaks down from the Greek — klero for chance because no one was previously sure if these plants had any medicinal value and dendron, meaning tree.

Sometime during the 1990s, taxonomists decided to reclassify the genus Clerodendrum and at the same time, reduce the number of known species from 400 to about 150 and re-group many former Clerodendrum to the genus Rotheca – plants known for a stinky quality when the stem is crushed. The purpose of pointing this out, is that many books upon which we horticulturists rely on for identification, still erroneously call some of these beauties Clerodendrum. In the end, it was not merely the physical characteristics that are easily observed, but it is the plant’s DNA that has the final say. In the count of seven Clerodendrum in the Moonlight Garden, at least two are now Rotheca (the Blue Butterfly Bush and the Musical Notes, which are discussed further below).

Why grow Clerodendrum? Because they have spectacular flowers! When not in bloom, most Clerodendrum do not offer much in the way of plant structure or foliage – for that reason, when they are added to our gardens at Edison Ford, they are often placed behind more attractive foliage or blended well into the landscape where the sometimes deciduous shrubs can hide until they are ready to burst forth with a symphony of flowers. Clerodendrum have origins in tropical Asia and sub-Saharan Africa and for the most part, the species share the same care regimen and are right at home in 9b-11 USDA zones. They will flourish in rich soil, but it must be very well drained as they require lots of water, particularly during our dry winter months. Morning sun in Southwest Florida is fine, but they should be protected from direct, western sun, especially during the summer.

Many Southern gardeners are already familiar with the Starburst Clerodendrum or Fireworks Clerodendrum (Clerodendrum quadriloculare).* Reaching the size of a small tree, its distinctive foliage with dark green on top and purple underside is enhanced when it’s bright pink starbursts open in early spring. If your garden can support a small tree-sized Clerodendrum, then Starburst, a favorite of hummingbirds and butterflies should be included. We do recommend that you give it a good pruning after the completion of flowering to prevent this handsome shrubby tree from becoming top heavy.

Both Flaming Glory Bower* (Clerodendrum splendens) with its bright red blooms and red Bleeding Heart Vine,* (Clerodendrum x speciosum) which has dark glossy foliage and a rich combination of red and pink flowers can sucker easily and spread rapidly in their happy place. According to Leu Gardens in Orlando, the red Bleeding Heart Vine is found in many old landscapes in South Florida but is not commonly offered for sale. It is believed that Mina Edison may have initially planted this vine here at the Edison homestead and it is presently in bloom along the southern wall of the Moonlight Garden where it pairs beautifully with a Brazilian Red Cloak* shrub (Megaskepasma erthrochlamys).

As tropical plants, many Clerodendrum species may appear to die to the ground in the event of a frost, though they will return in the warmer summer season. If you would prefer a less vigorous Clerodendrum for your landscape, there are several other species worth considering that are small shrubs or gentle vines, all with stunning flowers. The Bleeding Heart* (Clerodendrum thomsoniae) is an excellent perennial to grow in a large pot, especially with a trellis. Like many fast-growing plants, it loves water, a well-drained pot, and for best blooms, regular feeding. Prune after blooming to shape your plant, and a light prune throughout the season will keep it attractive. This Clerodendrum does well when slightly pot-bound and is not known to have any toxic effect on people or pets. The Northern version of Bleeding Heart, (Dicentra spectabilis) cannot be grown as a perennial in Southwest Florida. Pagoda Clerodendrum* (Clerodendrum paniculata) is another good choice for a planter. With bright red, pyramidal shaped flowers, this Clerodendrum can be aggressive in the ground, but is easily controlled in a pot. Blooming from spring to fall, and featuring very large leaves, this is a sure conversation starter.

Clerodendrum produce their flowers in a raceme form, also called a panicle, akin to a cluster of individual flowers. They may be upright or pendulous and their common names frequently refer to the flower’s appearance before blooming or after blooming. For example, Clerodendrum minahassae, can be called Fountain Clerodendrum* based on the appearance of its flowers and Starfish Clerodendrum, for the remaining starfish of sepals with a dark blue center seed pod after the petals have all fallen. The size of a large shrub, the Fountain Clerodendrum is found just outside the back door of Thomas Edison’s study. Originally brought to the United States by David Fairchild from Minahas Province in China in 1940, this Clerodendrum is also known as Fairchild’s Clerodendrum.

With the intention of the Moonlight Garden to feature lots of white flowers, the inclusion of Bridal Veil *(Clerodendrum wallichii) was a must in this garden, as it is the site of many intimate weddings. In the far corner of the garden, there is a high reaching vine which has entangled itself beautifully with the pink Bougainvillea and purple Queen’s Wreath and is one of a few plants in nature with a true-blue color – the Blue Butterfly Bush* (Rotheca myricoides Ugandense, formerly Clerodendrum ugandense) named more for the shape of its flowers than as a butterfly attractant. It is a lanky vine that best blends into a landscape, rather than be featured as a stand-alone plant. Its beautiful panicles of dark and light blue flowers will burst through, most of the year, except during the coldest weeks. Musical Notes,* another white species, receives its common name from the appearance of its unopened flowers; and again, it is now Rotheca microphylla (formerly Clerodendrum incisum). No doubt all these names can clog the brain, but we aim to provide the most accurate information we can – especially when our gardeners visit nurseries and growers and will encounter both names being used interchangeably.

Henry Ford liked to visit his friend and often joined in celebration of Edison’s birthday on February 11. So, it is quite fitting, that from December through June, there is a curtain of cascading racemes that resemble hanging light bulbs before reaching a full bloom along the exterior east wall of the Moonlight Garden. Known by many common names, such as “Indian Beads,” or “Chains of Glory,” we prefer to know Clerodendrum schmidtii (interchangeably called Clerodendrum smithianum) simply as the Lightbulb Clerodendrum.* This tall shrub border is just beginning to develop its flowers, so be sure to visit us this month and bring your camera!

Robert Halgrim

Robert C. Halgrim was an influential figure who worked very closely with Thomas Edison and made lasting impacts on important organizations throughout Fort Myers. He was born on September 9, 1905, in Humboldt, Iowa, and moved to the City of Palms – Fort Myers’ nickname – with his family as a young boy. His father, Conelius Halgrim, decided to move the family to Southwest Florida to grow castor beans, which yielded castor oil needed for airplane lubrication. Conelius obtained a contract from the Government and bought more than 1,000 acres of land at $1.25 per acre for his plantation during World War I. Today, this is the location of the Lee County Civic Center, which is used to

host a variety of public events.

Col. Halgrim also owned and operated the Court Theater, located in the Patio de Leon in downtown Fort Myers. As a teenager, Bob Halgrim worked at the theatre collecting tickets, where he met Thomas Edison for the first time. According to the Fort Myers Press, the world-famous inventor would attend showings of silent films two times a week during his winter vacations after the theatre opened. Halgrim would inform Edison when a new feature arrived, and the inventor typically brought groups of friends and family members to the first screening. Edison would sit in the first row by himself eating peanuts and his guests sat further back in the middle rows.

Halgrim began working for the Edisons in 1926. Two of Thomas and Mina Edison’s grandchildren, Jack and Ted Sloane, accompanied the couple on a trip. Mina Edison anticipated their stay with the two boys (ages 9 and 7), so she contacted the local Scoutmaster of Troop 1 to hire a young man to look after them. The Scoutmaster gave Mina the names of two well-known men in the community he thought would be a good fit, Robert (Bob) Halgrim and John Woolslair. Halgrim was a former counselor at Camp Jungle Wild (later Camp Ropaco) in Alva near the Caloosahatchee River. Edison was also very impressed with the young scout when he met him at the theatre, so they hired Robert to look after the boys. They did many activities together at Seminole Lodge, including fishing off the pier, sailing and canoeing in the Caloosahatchee River, and exploring Yellow Fever Creek.

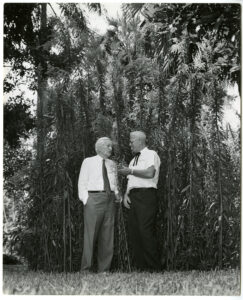

Charles Edison and Bob Halgrim stand in front of Goldenrod, the plant Edison found the most success with during his search for a natural source of rubber in the United States.

On a nice warm day, the teen spent time giving the boys lifesaving and swimming lessons at the Edison’s pool, one of the first residential pools constructed (in 1910) in the City of Fort Myers. Not only did Halgrim spend time with the Edisons in Fort Myers, but he traveled with the family to the Sloane’s summer house at Fisher’s Island. At the time, Thomas Edison was searching for a natural source of rubber that could be produced in the United States. The world-famous inventor’s goal was to produce an emergency supply of rubber that could be used for military equipment. Halgrim assisted with this project and collected plant specimens that were tested for rubber content at the Edison West Orange New Jersey lab.

After Halgrim graduated from Fort Myers High School in 1926, he continued conducting research at the Edison Botanic Research Laboratory in Fort Myers, the headquarters of the rubber project. Mina Edison placed a high value on education and wanted Robert to attend college; however, Edison preferred that he work for him fulltime. The young man later attended Cornell University with Mina Edison’s help, where he studied horticulture. While he was at Cornell, Robert frequently visited Thomas and Mina’s Glenmont

estate and stayed in their son, Theodore’s room.

Charles Edison is driven by Robert Halgrim in a Model T through the streets of Fort Myers during the 1967 Edison

Pagent of Light Parade .

According to an oral history conducted by Florida Gulf Coast University, Mrs. Edison gave the young man $200 to help him feel better about this decision since Edison was not in agreement. In 1929, Edison convinced Halgrim to return to his lab in Fort Myers and develop a rubber plantation on the east side of the property. The former student recalled that Edison made his employees feel at ease, calling them by their first names. Many of the staff did not feel like they were working with a living legend and appreciated that they could share a couple of laughs together on occasion. While Edison spent countless hours on his research, Halgrim took the time to care for his mentor, bringing him meals every few hours.

After Thomas Edison passed away in 1931, Mina Edison searched for ways that she could honor her husband’s legacy in Fort Myers. She arranged to donate Seminole Lodge to the City of Fort Myers in 1947 for $1 in Edison’s honor and to educate the public on how he impacted the community. When she made the agreement with the city, Mina requested that Bob Halgrim be selected as the first curator of the property. Halgrim agreed and a few months later, the estate was open to the public.

As Curator, Halgrim made the decision to develop a museum filled with artifacts and historical collections related to the Edison family. He wrote to and visited many sites across the country that could possibly loan items to display in the exhibits. Some pieces they acquired were donated, and others were bought by Robert Halgrim and the City, including antique phonographs and cars. The Museum officially opened on February 12, 1966, and Edison’s son Charles had the distinct privilege of being the guest speaker at the event. When the site first opened, no more than 30,000 people visited a year – compared to more than 220,000 visitors annually now.

Although he never graduated from Cornell University, Robert Halgrim received an honorary certificate from the college in April, 2005 for his achievements and dedication to developing Edison and Ford Winter Estates into the site that it is today. Throughout his life, he was also an active member of the Ft. Myers Chamber of Commerce, Edison Pageant of Light, Lions Club, and founding member of the Fisherman’s class at the First Presbyterian Church.

Today, visitors can see thousands of artifacts in the museum and can take a tour to learn more about the history that makes this cultural gem so unique!